Summary

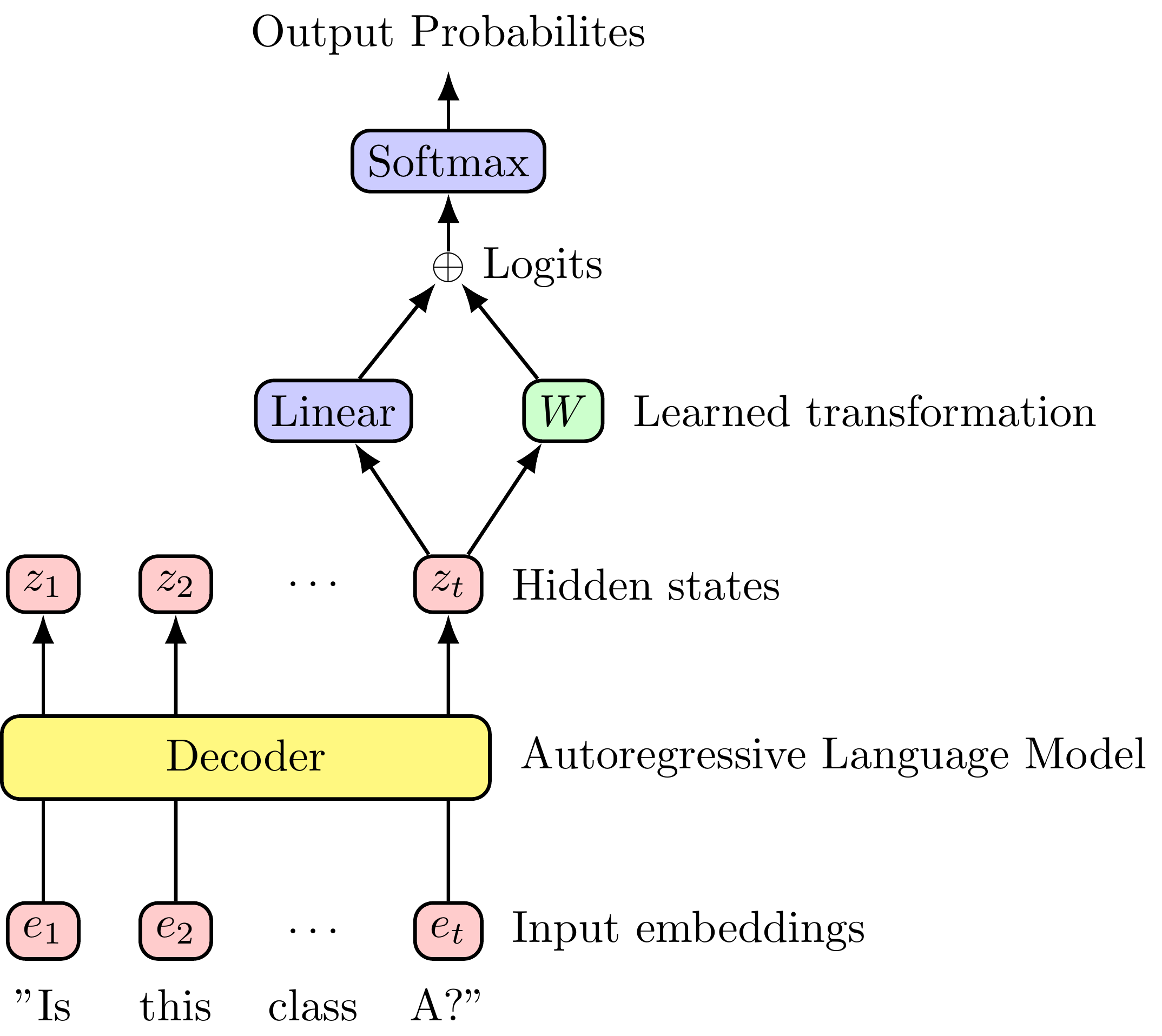

In this post I show how to linearly fine-tune a large language model (LLM) using a closed-form solution, based on the Moore-Penrose Inverse. I will focus on the special case of binary classification because the changes in output are easier to interpret. The new linear transformation \(W\) is shown in figure 1 (green).

About Fine-Tuning

Large Language Models (LLMs) are great baseline models for zero-shot classification, i.e. without any labeled examples. However, one often has a small labeled dataset \(D\) and is interested in improving the performance over this baseline. In the few-shot setting, some labeled examples are provided in the prompt for the model to learn in context. To improve upon this setting, the next step is to fine-tune the model on the labeled dataset.

There are different ways to fine-tune LLMs. For example: optimizing all network parameters, optimizing only the parameters of the final layer, or freezing all parameters but introduce a new smaller set of tunable parameters (Hu et al. 2021). In this post, I focus on the simple case of fine-tuning the last linear transformation, because I’m interested in interpreting the changes to individual logits and probabilities.

Binary Classification

I also focus on binary classification specifically. This means that the model must only answer yes/no or 0/1 to the prompt. This setting is easier to interpret with metrics like precision, recall or the \(F1\) score. Furthermore, in the binary case we can interpret how the fine-tuning procedure affected the model by inspecting the answers that flipped between yes/no and vice-versa (Dutta et al. 2024).

In terms of computation, we will see that the problem structure of binary classification can be leveraged to compute a closed-form solution efficiently. As shown in Figure 1, I add an additional linear transformation \(W\) before the softmax, and solve for it using the Moore-Penrose Inverse. This is mathematically equivalent to training \(W\) with gradient descent, but without all the iteration.

Closed-Form Solution

In underbraces, I’ve written the dimension of the matrices and vectors. In the original language model, the probability vector \(y\) has the same size of the vocabulary \(V\), and is given by:

\[ \begin{aligned} \underbrace{p(y | x_{1:t})}_{(1,V)} &= \text{softmax}(\underbrace{\text{logits}_t}_{(1,V)}) \\ &= \text{softmax}(\underbrace{z_t}_{(1,d)} \underbrace{A}_{(d,V)}) \end{aligned} \]

where \(z_t\) is the hidden state for the last token, and \(A\) is the weights the last linear layer (no bias is included as in Chowdhery et al. (2023)). The loss for this model is defined as the distance between these probabilites and our true labels, which is a set of binary labels \[D = \begin{bmatrix} d_1 \\ \vdots \\ d_N \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{(N, 2)}\]

With fine-tuning, we modify the probabilities that the LLM assigns to the tokens for yes/no from \(p\) to \(p_a\) (adapted probabilities). The role of \(W\) is change the logits that are passed to the softmax function. We tweak \(W\) to approximate the dataset \(D\) with the adapted probabilities \(p_a\):

\[ \begin{aligned} p_a(y | x_{1:t}) &= \text{softmax}(\text{logits}_t + z_t W) \\ \implies \underbrace{\log p_a}_{(1, V)} &= \underbrace{\text{logits}_t}_{(1,V)} + \underbrace{z_t}_{(1,d)} \underbrace{W}_{(d,V)} \end{aligned} \]

In vectorized form (one row per datapoint \(N\)) this can be written as:

\[ \begin{aligned} \underbrace{\log P_a}_{(N,V)} &= \underbrace{L_t}_{(N,V)} + \underbrace{Z_t}_{(N,d)} \underbrace{W}_{(d,V)} \end{aligned} \]

Solving for \(W\) exactly is only possible for squared invertible matrices \(Z_t\). However, \(W\) is rectangular (size \((d, V)\)), so this problem is solved approximately by minimizing the squared distance:

\[W = \arg \min_W || (\log P_a - L_t) - Z_t W ||^2_2 \qquad (1) \]

This is a least squares problem, whose solution is given by the Moore-Penrose Inverse.

\[W = (Z_t^T Z_t)^{-1} Z_t^T (\log P_a - L_t)\]

Or equivalently, by solving the following linear system of equations with \(V\) columns (But see note on numerical stability 1).

\[W = \text{linsolve}(\underbrace{Z_t^T Z_t}_{(d,d)}, \space \underbrace{Z_t^T (\log P_a - L_t)}_{(d,V)}) \qquad (2) \]

Runtime

Each linear system takes \(O(d^3)\) to solve, so solving \(V\) of these systems is prohibitively expensive (\(V=128k, d=4k\) in LLama3 8B). (But see note on repeated linear solves2). However, we can exploit the structure of the binary classification problem, by only evaluating the logits \(L_t\) and probabilities \(P_a\) for the yes/no tokens. This reduces the size of the probability matrix \(P_a\) by 4 to 5 orders of magnitude, from \((N,V)\) to \((N,2)\). Similarly, the learned matrix \(W\) shrinks from size \((d,V)\) to \((d,2)\).

As a result, we need to solve only 2 linear systems, each with runtime constant in the vocabulary size \(V\) and in the number of datapoints in our dataset \(N\), but proportional to \(O(d^3)\). As an added benefit of evaluating only the yes/no logits, the output of the fine-tuned model is compliant by design, as it cannot output any other logits other than for yes/no.

To solve for \(W\) either using eq (1) or eq (2), we plug in our dataset \(D\) for \(P_a\), since both matrices have the same size.

Inference

At inference time, the matrix \(W\) stays constant, while the logits change for each input.

\[ \begin{aligned} p_a(y|x_{1:t}) &= \text{softmax} \{ \text{logits}_t + z_t W \} \\ &= \text{softmax} \{ z_t A + z_t W \} \end{aligned} \]

Next Steps

In the next post, I will show an implementation of this method in PyTorch, and interpret how linear fine-tuning changes the outputs of the original LLM. I am interested in the flips between yes/no outside of the small fine-tuning dataset \(D\), and particularly on the boundaries of the dataset, and how this pertains to generalization. Stay tuned! :)

References

Footnotes

2024-09: The matrix \(Z^T Z\) is positive definite, so it is in theory efficiently invertible using the Cholesky decomposition. However, its condition number \(\kappa (Z^T Z)\) is squarely proportional to the condition number of \(\kappa(Z)\). This can lead to numerical instability when solving the linear system. In fact, I stumbled upon numerical instability while implementing this in linear system in PyTorch, which lead me to use an \(L_2\) regularization term. See Source.↩︎

2024-09: It turns out that solving a linear system with \(V\) columns on the right-hand side can be done cheaper than in \(V \cdot \frac{2}{3} d^3\) flops. To solve \(A X = B\) (with \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{d,d}\) and \(X, B \in \mathbb{R}^{d,V}\)) the factorization of \(A\) requires \(\frac{2}{3} d^3\) flops, but it only has to be done once. After that, solving for each of the \(V\) columns of \(B\) costs \(2 d^2\) flops each. So the total flop count is \(\frac{2}{3} d^3 + V \cdot 2 d^2\). This is a significant improvement over the naive approach. See (Watkins 2004, 77–78).↩︎