TL;DR: Tiling is a technique used to reduce the number of memory accesses performed during matrix multiplication. We see how it improves compute intensity and how it speeds up the matrix multiplication operation, not only on CPUs, but also on GPUs. I also provide a simple implementation of tiling in CUDA C.

Matrix Multiplication Recap

Matrix multiplication, where \(AB = C\), computes each element of \(C\) as:

\[C_{ij} = \sum_{k=1}^n A_{ik} B_{kj}\]

For simplicity, assume \(A\) and \(B\) are square matrices of size \(n\). Below is basic pseudocode for the operation, which involves \(2n^3\) floating-point operations (flops), because of the triple nested loop:

The code is correct, but it is inefficient in terms of its memory access pattern. Let’s see why.

Compute Intensity

Besides the count of flops, the performance of a matmul is also determined by the memory access pattern. The matmul has to fetch data from main memory into a fast cache (L1 or L2), compute, and then return the result to main memory. This roundtrip is time-consuming, and the cores can become idle waiting for the data from main memory. If so, the memory bandwidth becomes the bottleneck of the algorithm.

Key Concept: Compute Intensity. The compute intensity ratio, defined as flops per memory transfer, indicates whether an algorithm is limited by memory bandwidth or compute power. This concept originates from the Roofline model (Williams, Waterman, and Patterson 2009).

To boost performance, maximize compute intensity by reducing memory transfers per flop.

Memory Access Analysis

Naive Memory Access

In the naive approach, computing \(C_{ij}\) requires fetching \(n\) elements from \(A\) (a row) and \(n\) elements from \(B\) (a column). That makes \(2n\) memory accesses. \(C_{ij}\) is computed as the dot product of the row and the column, which requires \(2n\) flops (1 mult and 1 add, \(n\) times). Thus, the compute intensity is: \[ \text{Compute Intensity} = \frac{\text{flops}}{\text{memory transfers}} = \frac{2n}{2n} = 1 \]

Can we do better? In this naive implementation, we are performing redundant memory transfers: For example, to compute \(C_{11}\), and \(C_{12}\), we fetch the first row of \(A\) twice from main memory.

Optimal Memory Access

If our cache was (theoretically) large enough, we would transfer all elements of \(A\) and \(B\) into the cache at once (\(2n^2\) transfers) and perform the full matrix multiplication (\(2n^3\) flops).

\[ \text{Compute Intensity} = \frac{\text{flops}}{\text{memory transfers}} = \frac{2n^3}{2n^2} = n \] The larger the matrices, the higher the compute intensity.

Assuming a matrix size of \(n=10,000\), the naive approach does 1 flop per memory transfer, while the optimal approach does 10,000 flops per memory transfer. This would result in a 10,000x speedup, assuming memory bandwidth remained the bottleneck.

A Middle Ground: Tiling

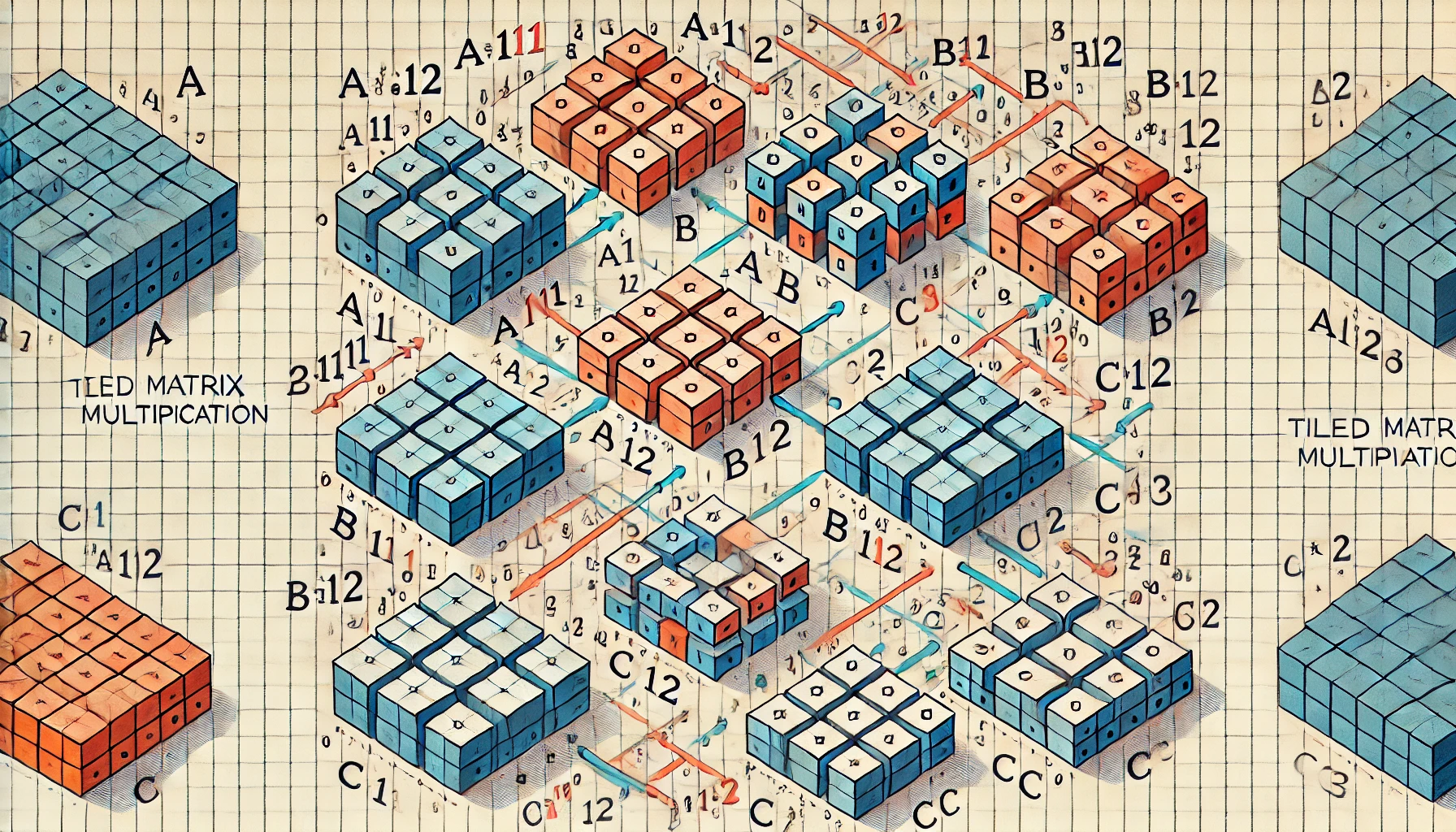

Since caching entire matrices is impractical, we divide matrices \(A\) and \(B\) into smaller square blocks of size \(r\), called tiles, perform block-wise multiplications, and aggregate the results.

But how does block-wise matrix multiplication work? Let’s go through an example to gain some intuition. We break the matrices \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\) into 4 blocks each (2x2). Each of these blocks has size \(n/2\).

\[ \begin{bmatrix} A_{11} & A_{12} \\ A_{21} & A_{22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} B_{11} & B_{12} \\ B_{21} & B_{22} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} C_{11} & C_{12} \\ C_{21} & C_{22} \end{bmatrix} \]

To compute an submatrix \(C_{ij}\), we multiply the corresponding blocks of \(A\) and \(B\) and sum the results. For example:

\[ C_{11} = A_{11}B_{11} + A_{12}B_{21} \]

In pseudocode this translates to the code below.

n_blocks = n // r

for i in range(n_blocks):

for j in range(n_blocks):

for k in range(n_blocks):

C[i][j] += A[i][k] @ B[k][j]Note that the entry C[i][j] is now a block matrix rather than a scalar, and the @ operator denotes matrix multiplication, rather than scalar multiplication. Line 5 of the code above is loading blocks of size \(r^2\) from \(A\) and \(B\) into the cache, which takes \(2r^2\) memory transfers. Then, it multiplies the two blocks, which requires \(2r^3\) flops.

\[ \text{Compute Intensity} = \frac{\text{flops}}{\text{memory transfers}} = \frac{2r^3}{2r^2} = r \]

Assuming a block size of \(r=100\), the naive approach does 1 flop per memory transfer, while the tiling approach does 100 flops per memory transfer. This would result in a 100x speedup, assuming memory bandwidth remained the bottleneck.

It should be clear that \(1 \leq r \leq n\). Setting \(r=1\), we recover the naive approach, while setting \(r=n\) we recover the optimal approach. The table below compares the performance of the different methods. Note that for the tiled method, the flops and memory transfers are measured per block, rather than per matrix.

| Method | Flops | Memory Transfers | Flops/Memory Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | \(2n^3\) | \(2n \cdot n^2\) | \(\frac{2n^3}{2n \cdot n^2} = 1\) |

| Tiling | \(2r^3\) | \(2r^2\) | \(\frac{r^3}{r^2} = r\) |

| Optimal (Theoretical) | \(2n^3\) | \(2n^2\) | \(\frac{n^3}{n^2} = n\) |

Tiling on GPUs & CUDA

GPUs have a large number of cores, which can quickly process the data arriving from memory. Therefore, the memory bandwidth is likely to be a bottleneck in matrix multiplication on GPUs. To relieve the pressure on the memory bandwidth, it’s necessary to reduce the number of memory transfers by using the tiling technique.

How is this actually implemented on a GPU? The code block below shows a simplified tiled matrix multiplication in CUDA C. The key idea is that the cache is explicitly written and read using CUDA shared memory. This is the equivalent to a user-managed L1 cache. The keyword __shared__ defines an array used as cache. The variables row and col indicate what element of the matrix \(C_{ij}\) the function computes. Line 13 is the loop over blocks. Lines 15-16 load the data from main memory into the cache. Lines 22-24 perform the dot product and accumulate the result. Finally, line 31 writes the result back to global memory. The function __syncthreads() is a CUDA synchronization primitive to avoid a race condition between threads.

__global__ void tiledMatMul(float *A, float *B, float *C, int n) {

// Define shared memory arrays (cache)

__shared__ float A_block[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

__shared__ float B_block[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

// CUDA thread variables

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

float C_ij = 0.0f;

// Loop over the blocks

for (int t = 0; t < n / TILE_SIZE; t++) {

// Transfer data from main memory into the cache

A_block[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = A[row * n + t * TILE_SIZE + threadIdx.x];

B_block[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = B[(t * TILE_SIZE + threadIdx.y) * n + col];

// Ensure data transfer is complete before proceeding

__syncthreads();

// Matrix multiply both blocks

for (int k = 0; k < TILE_SIZE; k++) {

C_ij += A_block[threadIdx.y][k] * B_block[k][threadIdx.x];

}

// Finish multiplying the blocks before overwriting the cache next iteration

__syncthreads();

}

// Transfer the result back to global memory

C[row * n + col] = C_ij;

}The CUDA code is more complicated than the pseudocode, but it makes the cache usage explicit. To run the code look at my example on Github, which has Makefile for compilation and execution. If you want to see a more complete version, you can find it in the book by (Kirk and Wen-Mei 2016). They describe other techniques to optimize algorithms on GPUs, like memory coalescing, minimizing control divergence, and thread coarsening.

Conclusion

Tiling is a practical optimization technique for improving matrix multiplication performance by minimizing memory transfers and maximizing compute intensity. We saw how the memory access pattern affects the performance of matrix multiplication, and how tiling is implemented concretely in CUDA C.

Acknowledgement: The author is funded by the Bavarian Research Institute for Digital Transformation (bidt) and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

References

Citation

@online{ruiz2024,

author = {Ruiz, Tomas},

title = {How {Does} {Tiling} {Speed} {Up} {Matrix} {Multiplications}

on {GPUs?}},

date = {2024-12-23},

url = {https://tomasruizt.github.io/posts/tiling-for-matrix-mult/},

langid = {en}

}